Where does the mind of the prime minister wander to when what little sleep she is afforded just refuses to arrive?

Is there an essential place, a composite of some abstract idea of what Britain is and who the British are, where her thoughts come to rest?

Their lives so different, their smell so strange, their concerns so vapid compared to those of high office. What do they do? She ponders. But she knows that question is too frail to linger. The people want something done. And she is the doer in chief — the expression of their pragmatism, their will to muddle on, their inarticulate sense of duty.

Perhaps May wishes she could wander out into the gloaming incognito, like Shakespeare’s King Harry before Agincourt, and find out what the people really think in order to return to her tent with some harsh truths and burning new purpose for the next morning.

But hers is a task more terrible than trying to gub the overweening French with a few stout yeomen. The task is impossible: to make something fit (the British constitution) with a concept (popular sovereignty) that it evolved in opposition to.

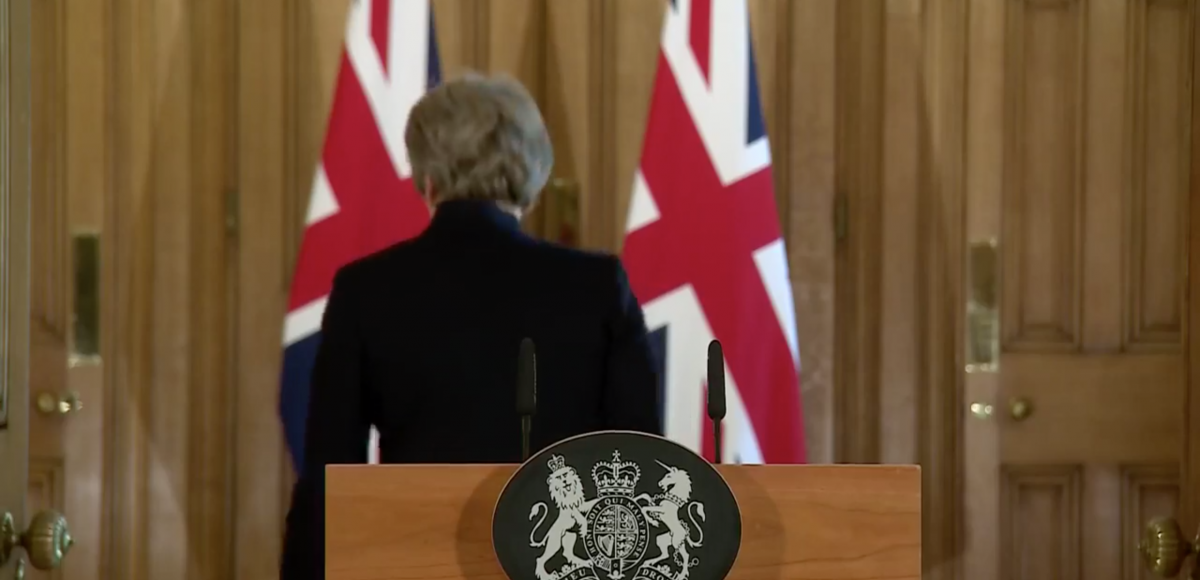

Politicians, successful ones at least, learn to be adept at roving amongst the people. The most skilled paint an authentic impression that they’d gladly do so all day. But the gulf has never been so palpable as it is in these strange listless days of crisis and collapse. Here is a haunted woman whose every fibre seems to scream to be left alone, to be off in the hills, the embodiment of that great British mantra: anything for a quiet life.

Partly because of this desire to be left undisturbed, in private, the people in Britain are an odd crew. In France Macron can respond to the Gilet Jaunes with a ‘grand debate’ partly because the people are recognised as legitimate actors there. All that British politics can offer is a faint focus group echo of the voice of the ‘doorstep’ from a lectern. The people are not doers. They send messages to the doers: hence the mass confusion of signal and noise that the Brexit crisis has become.

Above all, it seems, they want her to “get on with it.” They want it finished. This is her task. In a republican twist on Thursday, she spoke to them directly, spurning the institutions, the cultures and the party structures upon which her power is built. They are less important, she told the audiences at home, than you and me. My power is your will.

“…you the public have had enough,” she told us. Where, you wonder, did her imagination place this notional “us” as she stared down the lens? What did we look like? How would we respond to the substantial amount of insight she was about to share about how we all felt?

But rather than a lens, perhaps for a moment she saw a mirror. Because what was staring back, her address seemed to tell us, was a mass of worn faces, a bit put out at having to attend to this proclamation in the first place. Above all else, the Britain that May saw staring back at her was tired.

“You are tired of the infighting. You are tired of the political games and the arcane procedural rows. Tired of MPs talking about nothing else but Brexit when you have real concerns…”

It’s the work of more sensitive political structures that the UK’s to articulate what the cause of that tiredness might be. If May did see her own exhaustion laid out before her in row upon row of living rooms from Maidstone to Mallaig, did she register a glimmer of her own culpability, or her party’s, in this great national fatigue? We may never know, the times are too torrid for the thought of memoirs.

Yet decades of precedent demanding the decisive exercise of executive power by her office discourage most forms of reflection. This, in turn, makes it hard to love the people. The people can be fickle you see. They’ll tell you one thing, via one advisor, one day, and something entirely contradictory, via another, the next.

Tasked with playing the role of people’s tribune at this moment of impending revolution, she must now be a populist, railing against a dithering establishment frustrating the popular will. She must connect a live wire to the people — despite a mesh of obstacles assembled over three decades as a professional politician. Where might she begin to look for them? There is family, there is the church, there is the CA, there is business, then there are the civil servants, the ministerial visits, the odd constituent.

It’s a cruel joke inflicted on her by the mendacious and callous political movement to which she belongs. Be a populist Theresa. You are among the least equipped individuals in the land to pull it off. But that doesn’t matter. The authentic 17,410,742 are the basic, indeed the only, democratic truth holders. The 16,141,241 crowd the picture, weary too. Perhaps, just, willing to go along with her, out of expediency. A homeland populated with commuters, not workers. Of service users, not citizens. ‘Why can’t somebody else fix this?’ They groan.

‘You want this stage of the Brexit process to be over and done with. I agree. I am on your side.’ She responds. Our side. A national side. A happy few.

Britain, like all old empires, is still uneasy at peace. The ties that bind are a kind of contingency, a willingness to mobilise against external threat. The long peace heralded with 1998 and the Good Friday Agreement turned out to be a short one, as though there was a searching need to be deployed again the minute Blair signed it. Because that’s who “we” are, a defensive compact of peoples.

Fittingly, for a martial society, the British have tended to only emerge as a cohesive people, with clear social demands after periods of extended conflict. Unity of purpose, and the clear popular will required for radical shifts like Brexit, have traditionally required blood sacrifice and a demobbed mass of young people to shift the scales.

Little wonder that the people are thought to want clear resolutions. There are sides to be chosen and there are winners and losers, pity those who choose wrongly.

Theresa May and her party represent Britain’s winning classes. This base has brought them a remarkable resilience. 40 years in, the hegemony of the British right is starting to collapse in on itself. Theresa May is not simply an unerringly bad Prime Minister with the wrong skills at the wrong time. Her premiership represents a far more essential failure of British politics, a breakdown between government and the governed. Yet all the while, failure itself is unspeakable.

In life, people lose things all the time. Loss is mundane. On a day to day basis, most people who work in politics don’t experience a great clash of ideas and rival forces, instead, their work is a daily struggle to keep the show on the road. In that world loss is taboo — it means ritual humiliation.

The British political system cannot contain gradations of loss, or the grey areas of failed projects. The foundational reality of British democracy is that the winner takes all. This reality cannot be reconciled with the current national crisis in which everyone, ultimately, must lose something.