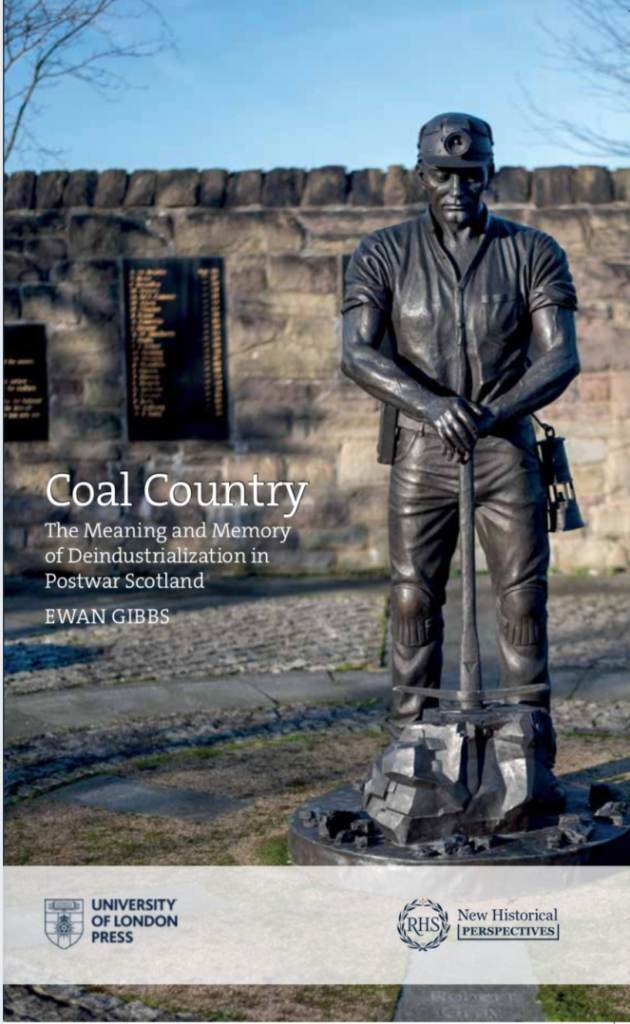

Christopher Silver reviews ‘Coal Country. The Meaning and Memory of Deindustrialization in Postwar Scotland’, by Ewan Gibbs.

In 2019 I traveled to three European mining regions: Silesia in Poland, the Ruhr Valley in Germany and Limburg, in the southern corner of the Netherlands. Common to all of these places was a strong image of the region in relation to the wider national community: each was considered both dirtier and rougher, but also more vital and self-reliant, than any other part of the country.

Much of this was premised on the common solidarity that emerges from the hazardous reality of working underground. Indeed, the Dutch term for miners, kompels, is a cousin of several words in European tongues for comrade, friend, pal. Partly because it demands such bonds, deep-cast mining lingers in regional and national identities like few other industries. It’s therefore fitting that, Coal Country, The Meaning and Memory of Deindustrialisation in Postwar Scotland, by Ewan Gibbs, is centred on Lanarkshire. The double meaning of ‘country’ as a specific industrial heartland but potentially the coal-fired nation too, is also significant.

Politically, the nation may be moving inexorably towards some form of independence. But in economic terms, widespread postwar anxieties that Scotland would be rendered a ‘branch plant’ economy have largely been borne out. The grinding failure of policy makers at Holyrood to develop a renewable energy supply chain are perhaps the most glaring example of a tacit acceptance that the Scottish economy will become less Scottish with each passing year. The stripping out of industrial capacity, in a world of labyrinthine global supply chains, is understood as an irreversible act.

In contrast, coal once marked out a nation as economically independent, an idea that was embodied in the strength of miners themselves. As several interviewees in this work of oral history articulate, this was about sacrifice (with particular reference to the dangers of working underground) and the status of coal as a base that ‘kept the country going.’

Underpinning coalfield politics is the now elusive concept of a moral economy – that miners worked a community resource, which also provided a broader public good, and thus deserved a fair deal which historically they’d often been denied. As an old mining anthem popularised by Dick Gaughan in the wake of the miner’s strike framed it, this was intimately related to the miner’s capacity to endure physical hardship: ‘What have you to show for working/Since your mining days began?/Worn-out shoes and worn-out miners/Blackened lungs and faces pale/Keep your hand upon your wages/And your eye upon the scale.’

Lanarkshire was also the site where postwar Scottish nationalism first arrived on the scene. Winnie Ewing’s landmark 1967 by-election victory, as Gibbs notes, heralded the arrival of the SNP as a significant political force in the region. This new political nationalism mirrored an increasingly national frame for coalfield politics, through the expansion of larger ‘cosmopolitan’ pits, decoupled from an immediate community or village, under nationalisation. The emergence of a national coalfield consciousness was underlined by support from the Communist led National Union of Mineworkers Scottish Area for devolution, which in turn was instrumental in swinging the STUC behind the campaign for devolution. Early talk of ‘mandates’ and deep failures of representation are presented by Gibbs as part of a lineage that runs from NUMSA through to familiar contemporary anti-Tory rhetoric . Today, Scotland’s dominant political parties are cagey about this legacy – but carbon politics undergirds the sleek postmodern façade of the Scottish Parliament.

An equally uncomfortable legacy can be seen in Lanarkshire today with its commuter belt housing, motorways and business parks, Police Scotland’s futuristic “crime campus” at Gartcosh. The former coal country can still claim to be a geographic, if not industrial, heartland. But it is also now a vacant space in the national imagination; a corridor between the country’s rival ‘global’ cities. Memories of what went on there were perhaps ritually erased from the nation’s imagination with the cooling towers at Ravenscraig. But at its best, Coal Country is a work of history which moves beyond the familiar symbols of deindustrialisation, and points instead to the rich legacy of mining in Scotland, an indelible stamp on the contemporary nation.

At one point, council tenancy rates of over eighty per cent could be found in much of North Lanarkshire. But as one resident of Bellshill points out, the traditional link between housing and work has been broken: ‘They’re seeing it as a town to build nice new houses in, absolutely, because it’s half way between Glasgow and Edinburgh so it gets you along the motorway. That was never what it was supposed to be about. That was never what Bellshill was.’ Success as a dormitory town, with service sector jobs and a dwindling high street, represents a deeper failure to honour the deal that the postwar moral economy offered, and which many older members of these communities still view as foundational.

The history that Gibbs assembles here is a long durée version of deindustrialisation rather than the ‘instant’ version associated with the eighties. Indeed, we can read the testimonies presented as an indictment of successive economic policies that have, across different political regimes and ideological assumptions, chased inward investment as a salve for the bruises of heavy industry’s contraction. Such investors, whatever the inducements, generally proved more skittish than they were supposed to in the grand narratives of Scotland reinvented as a light manufacturing hub. From Toothill to Silicon Glen, a whole series of promised industrial futures ended up on the scrapheap within the lifespan of the workers interviewed in this volume.

One of the most revealing passages of Coal Country offers reflections shared by a former miner who went on to work at Chungwha’s Taiwanese television parts factory near Airdrie. The plant was constructed with substantial public funds but closed within a decade. Anger at this policy failure was compounded by the experience of a decidedly anti-social workplace regime: twelve hour shifts, no overtime rate, and no union. More poignant still was the silence, contrasted with the noise and camaraderie of work in the mines – ‘ye werenae allowed to talk.’ The destruction of the moral economy of coal is premised on silence too: we no longer want to think or confront the noisome and brutal reality of capitalism: that it must always place a worker’s body on the line at some point, somewhere.

Readers of Coal Country might be surprised to find less emphasis placed on the secondary social consequences of deindustrialisation and the generational experience of mass unemployment. But this contrasts with the binary approach hammered home in so many cultural accounts: if you get rid of Docherty, you end up with Begbie. Indeed, it’s notable that the two unanticipated successes in Scottish fiction last year – Shuggie Bain and Scabby Queen – both feature mining communities and their struggles in the eighties in a far from flattering light. The familiar cultural terrain of Scottish masculinity – casting ‘ordinary’ working class communities as drab, tribal and singular doesn’t match the lived experiences collected in Coal Country. Instead, the book serves to counter the idea that working men are inherently violent, unless out by hard manual labour, that pit closures must mean villages going to the dogs, that industrial workers must be sheep-like in their solidarity. This book adds much needed nuance to accounts of deindustrialisation in Scotland. Crucially, Gibbs also looks at the changes in gender roles over the period, developing a richer account of the demise of the heroic masculine breadwinner. In post-pandemic Scotland, attention to questions of social reproduction and its transformation beyond the domestic sphere, could not be more timely.

Coal Country is particularly good at identifying the colour and vibrancy of Scottish mining culture. A chapter on the Scottish miners’ gala, a now defunct annual event that brought together aspects of traditional village celebrations with a strong internationalist agenda, captures this (over the years the event held in Edinburgh included guest speakers from North Vietnam and later South Africa).

Despite being a work of academic history, Coal Country still points towards a troubled future for carbon politics in Scotland. In direct terms this is the Scottish Government’s faltering commitment to a Just Transition away from carbon based industries. But this agenda itself is dogged by the tough reality outlined by Indian novelist Amitav Ghosh. Namely, that the inherently labour intensive nature of deep cast coal mining became linked with movements for the establishment of modern democratic rights around the turn of the last century. This in turn informed capital’s shift to the isolated wells and pipelines of global oil production, which could flow from the periphery uninterrupted by the demands of working people.

It was a similar calculus, some seventy years later, which destroyed the moral economy of coal in Britain and offshored the work (and the emissions) to Poland and ultimately Asia; the workforce was too assertive an obstacle to monetarist policy. In contemporary Scotland, where former miners in Fife now watch Indonesian windfarm components sail up the Forth, it seems incongruous to ever think that the agenda for Scottish self-government was once bound up with economic development. Increasingly, ‘What have you to show for working?’ becomes a question that Scots ask with bitterness at the embarrassment of fenced-off and privatised resources around them.

Coal Country demonstrates how the ‘aura of permanence’ – rooted in the physical scale of heavy industry on the landscape – turned out to be illusory. However, the book implies that there is a more resilient legacy in the form of shared memories and lived experiences of workplace democracy and moral economy: a lifeworld of solidarity that we forget at our peril, kompels.