There’s something magical about living in Edinburgh as the festival draws to a close – something far more poignant than mere relief that the bins will stop overflowing, or that you’ll no longer have to factor in an extra 20 minutes to cross the span of Hunter Square.

Having worked several odd jobs at the festivals over the years: I recall them winding down, as autumn is tasted on the breeze for the first time, and with it the feeling of a more familiar city returning. For, as the bards tell us, no city is more definitively autumnal than Edinburgh.

But that welcome change was always tempered by a knowledge which seemed so certain: that this great glut of humanity would be back as sure as the summer itself. In the grand scheme of things the expectation of Edinburgh’s annual transformation was a small matter: but it is yet another marker of time that the pandemic has stolen.

It may only last for four weeks, but the festival is imbricated in all aspects of this place – it doesn’t simply align with a moment of seasonal change, it is a kind of elemental force in its own right.

An old friend used to respond to our habitually barren financial and romantic lives with the Micawbersish line – ‘the festival always turns something up.’

Somehow it always did. The sheer mass of new arrivals, the switch to a temporary 24-hour city, the weirdness, the spontaneity, offered a season that seemed to belong to more permissive and egalitarian times and places.

Loitering on the penultimate evening of the Edinburgh Book Festival earlier this week, I was thinking about my former festival days.

Watching the camaraderie of the staff and the gradual moves to take down the temporary apparatus of spectacle, I thought of the punishing hours, the madness of working to help put on something so vast. I observed the stalwarts of Edinburgh’s galleries and theatres, hale as ever, glance around in quiet acknowledgment that this year was a ghostly imprint of what had gone before.

To walk through central Edinburgh in August 2019 was to experience an ambient assault of invitation: but this year you had to furtively seek out any residue of the carnivalesque.

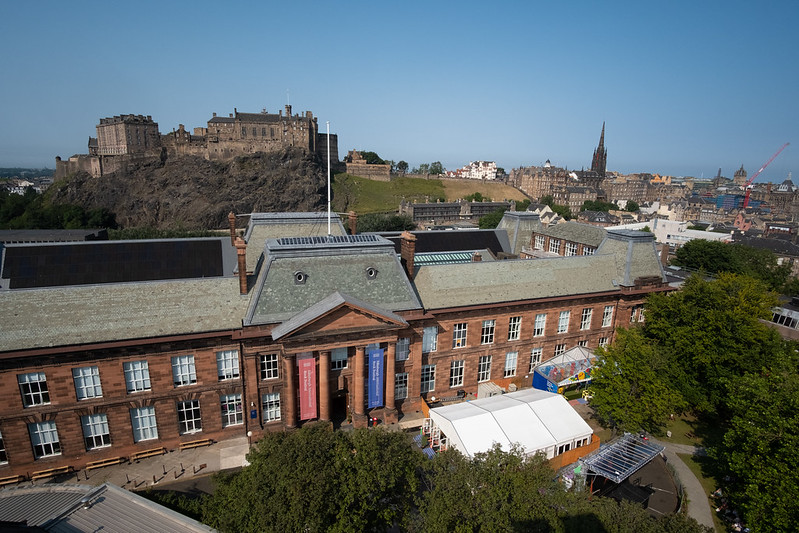

On the big screen at the Book Festival’s new home in the Edinburgh College of Art quad, a modest crowd, just too scattered to share each other’s’ responses, watched a team of theatre-makers interpret Kathleen Jamie’s prose variations, The Yellow Door.

Director David Greig pointedly noted that this five year long strand of work at the festival, Playing with Books, has been a much needed outlet for experimentation because ‘the world of theatre is chronically underfunded even outside the pandemic.’

Later, the woman who has overseen such cuts arrived and was met with a reverential hush. Culture is indeed extolled with great originality by our bookish First Minister, and like her counterparts in the south, her government ensured that the live arts were able to survive the unprecedented existential threat of the pandemic.

Instantly Consumable

But there is a deeper disquiet within Scottish culture that a palpably unrevived festival scene underlines.

What if the festivals, already experiencing a silent crisis prior to the pandemic, will simply continue to decline? What if they never return to their former glory and an already fragile Scottish cultural sector sinks with them?

Behind these concerns sits the great awkward question of whether Scotland’s cultural and political leaders really feel that there is the will, or demand, to reinvent the basis for these events. The festivals were founded with an existential mission to bring nations together after half a century of carnage, but there is no equivalent vision today.

The pandemic may be a crisis on the scale of global conflict – but the implications of recovery from it seem to point in the opposite direction – remoteness is sensible policy.

Without the magic of accessible international travel and its capacity to bring so many performers from so many places together; Edinburgh’s festivals are doomed. If this element gets discarded the city will end up like Prospero, realising, finally (in lines spoken on so many rickety stages, by so many over-enunciating students): ‘my charms are all o’erthrown,/And what strength I have’s mine own,/Which is most faint: now, ’tis true,/I must be here confined by you.’

The Olympics and the FIFA World Cup are the only events on the planet that attracted numbers equivalent to those that once attended Edinburgh in August. Events of such scale are great spectacles of over-consumption, fattened by years of complacent corporate greed, but they are also the holy-days and carnivals that make life in the global village purposeful. They allow us to watch humanity at its most graceful, skilful, dexterous and weird.

The problem is not the events themselves, but the way in which late capitalism has become ever more drawn to instantly consumable experiences; hungering for their potential as a repository for surplus capital. Large-scale events, recurrent, easily replicated and always instilling a thirst for more, are the ideal commodities of our time.

These qualities make the ‘immaterial’ products of the events and tourism sector ever more alluring, but they come with heavy material and social impacts on the localities where they take place.

Edinburgh has undoubtedly suffered from that boosterism, from a greed for exponential growth; perching its fortunes precipitously high above the pre-pandemic competition.

The festivals can also be understood as a seventy-four year process of gentrification; with the first wave landing in the fertile but seedy terrain of the post-war Old Town. Perhaps Edinburgh’s lightning-fast gentrification over the past three decades simply fulfils a pattern; familiar to so many increasingly expensive and exclusionary cultural capitals the world over. The recent controversies around the city’s UNESCO status and its struggles with overtourism stem from reaching material limits – this is a small city which has simply run out of space to colonise.

But the loss of Leith and Fountainbridge to the endless march of coffee shops and gastropubs is incidental. You could strip out Edinburgh’s culture scene tomorrow and these will remain. Art may be part of the first wave of gentrification, but its open and experimental forms can disappear just as quickly as they arrived.

It will take a kind of reverse engineering of this process; a decoupling of culture from boosterism and growth, to revive Edinburgh’s cultural status. There is a need for a new founding moment and vision equal to that proposed in 1947. Tragically, decades of austerity and neglect have hollowed out the institutions that might once have championed and instilled such fresh thinking.

Diminished

Wandering about this radically diminished festival, I found myself yearning for the strangest of things. I wanted to go and see something that would probably be terrible, but might, against all the odds, prove wonderous: I longed for Ibsen performed by geese in a paddling pool, or a musical interpretation of the life of Gladstone.

Sitting through the worst performances always brings that nagging sense that you will never get the time back: but it is the thrill of taking such a risk which underpins the remarkable spontaneity that only a live event can offer. That capacity to be a bit promiscuous with our time, to gamble it and play with it, is precisely what was taken from us all in 2020.

The pandemic has left us at sea when it comes to the heavy passing of time: we need art above all because it can seem to expand, circumvent or recast it. As Greig said of reading The Yellow Door for the first time, the work seemed to ‘make time exist where it hadn’t existed before.’

The illusion that witnessing a performance can offer us: that time can be conjured up, or restored, may simply be a baseless trick that fades when the lights go down. But in a sick world that needs to work like hell to heal itself – who would dare put a price on it?

Photo by Robin Mair/Edinburgh International Book Festival