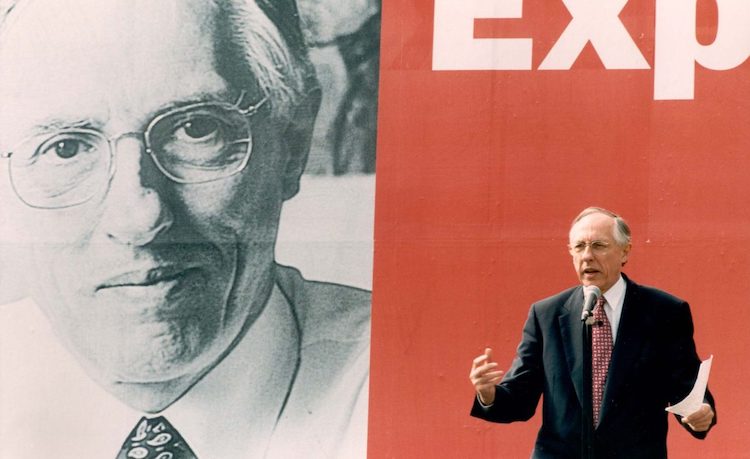

In 1968 a Labour MP sat down to co-author a pamphlet entitled ‘Don’t Butcher Scotland’s Future’ – a strident rebuke to the nascent force of Scottish nationalism. This was a moment when ‘hammering the nats’ became a key part of a good Scottish Labour man’s vocation, and the young Jim Sillars would prove to be no slacker in this regard.

The ensuing transformation of Sillars into an equally pugilistic proponent of Scottish independence is riddled with the lure of familiar enemies of monstrous proportions: nationalism, Thatcherism, Europe.

Like Thatcher herself, ‘a political heavyweight opponent,’ as Sillars would acknowledge in the House of Commons, politicians all too easily become defined by their ideological alter-egos. But when the demons are banished, neutered, or transformed, the oppositional hunt remains and coherent purpose ebbs.

Weaned in an era of cut and dry anti-Thatcherism, this is the psychological trap Scottish Labour now finds itself in. A desperate refusal to accept its ideological proximity to the SNP, and an insistence on seeing a nationalist demon in its place, is the main factor that has now led the party to seek its tenth leader at Holyrood in two decades. When the current race for the Scottish Labour leadership closes, the successful candidate should begin the long overdue process of listening to the many Scots who have moved from unionism to nationalism. There is much to understand.

However, Scottish Labour’s basic assumption, which events like Brexit have underlined, is that nationalism is invariably malevolent. The party seems to view the nationalisms now triumphant in London and Edinburgh as essentially different faces of the same troubling creature.

Find a new enemy

In addition to a new leader, the party needs to elect a new opponent, a new set of enemies that reflect actual political realities in Scotland, rather than those it finds more convenient or flattering. If it doesn’t reverse this latter attitude and seek instead some form of dialogue with Scottish nationalism, the trap will lead to its total demise. Anti-nationalism in Scotland has become a defensive force and has bred its own dark reactionary undercurrent.

As recent ructions within the SNP have shown, self-proclaimed civic nationalists aren’t necessarily civil, but generic, tepid anti-nationalism does nothing to move Labour beyond its radically diminished base. Instead, it prioritises a minor point of political theory above any interest in reaching out to an electorate which is, at the very least, increasingly sceptical about the fundamental claims of unionism. Labour has long walled-off engagement with the rich and varied political thought and tradition that has fed into Scottish nationalism, seeing only the basest instincts in political expression of emergent Scottish nationality. All of this is still occasionally underpinned by that most monstrous accusation of all – that the tartan zealots paved the way for Thatcher’s victory in 1979.

More recently, this basic anti-nationalist narrative has been undermined by UK Labour’s leaked strategy: wrapping itself in the union flag will be necessary to recover in the north of England. Then again, Labour stood in the 2015 General Election under the slogan, ‘One Nation.’ How such messages can be squared with revival in Scotland – where a majority of voters now support independence, and the Tories have established a seemingly resilient Tweed-Orange alliance – remains mysterious.

Municipal socialism and other variants

Modern Scotland was birthed in the context of an anti-Thatcherism that Labour translated into seemingly unassailable dominance north of the border. It built a base of support that embraced working- and middle-class Scotland, and out of this deep civic consensus, came round to full support of devolution. But Labour’s old dominance was also about the remarkably wide imprint that municipal socialism has had in Scotland. A stamp that is evident in every aspect of Scottish life: from education, to the urban environment, to the canny wielding of soft power and the quiet embrace of ‘small n’ civic nationalism.

Reluctance to confront steep decline has led to an internal myopia about the state of Labour in Scotland – now a residue of a political movement, but one that is still, remarkably, riven by factionalism. Success in pockets of wealthy anti-nationalist sentiment can be seen in Scottish Labour’s last remaining redoubt at Westminster: Edinburgh South, ‘Red Morningside’, is one of the wealthiest constituencies in the country. Many in the party, including those who defenestrated Richard Leonard, prefer a politics of unionism over a politics of class, for obvious reasons.

In 1980, around 60% of Scots lived in social housing. Today, roughly the same proportion are owner occupiers. This creates a politics which privileges those with assets, and shames those saddled with rents and debts. Constitutional politics has very little to say on this shift. However, Pauline McNeill’s Fair Rents Bill is a signal that the party can grapple with pressing concerns on terrain that still makes the SNP uncomfortable. If you’re on the side of those with the least, your enemies are simply those that exploit them: the nationalist/unionist divide becomes irrelevant.

People will of course tell you, on the doorstep, that the SNP government is stumbling: it has been in office for more than a decade. But to fail to understand that Sturgeon has always been ideally placed to speak to former Labour voters is an astonishing demonstration of tactical blindness. It also represents a significant lapse of institutional memory (if, indeed, there is a functioning institution behind Labour’s 23 MSPs at all). It was Labour that first realised the potency of ‘standing up for Scotland,’ and in some ways set the template for the kind of electoral dominance the SNP now enjoy.

Leaving me

This is perhaps best summed up by the prevalence of the ‘Labour left me’ refrain, which at points comes close to a founding narrative for the post-devolution SNP. It is hard to find evidence of any coherent effort to get those voters back, indeed, it’s not even clear if the party actually wants them. The consistent stance has been to view these erring electors as just so many estranged children, going through a phase. In 2010 Jim Murphy voiced the notion that Scots had ‘come home’ to Labour. Maybe he still thinks they still will, one day.

But the notion of ‘Labour Scotland’ remains surprisingly resilient. Each new Scottish Labour leader exists in the shadow of the doyen of devolution, Donald Dewar. Just as Dewar becomes ever more embedded as a kind of ‘father of the nation,’ so each of his successors has struggled to articulate why a Labour First Minister is a compelling option. Both candidates in the current leadership race are competing for the chance to rebuild and reclaim second place: there is no prospect of a Labour government in Scotland on the horizon.

As opinion moves behind independence, the focus on the process and legitimacy of a second referendum becomes key. It is this that has marked Monica Lennon out as a clear departure: a voice finally prepared to accommodate the 30-40% of Labour voters who support Scottish statehood.

But there is a wider agenda that should be built around support for self-determination: not just at the level of the nation, but in town halls and on the shop floor too.

Before that, Scottish Labour will only save itself by making its own declaration of independence, beyond administrative tinkering, from the wider UK structure. It must learn to speak with a distinctive voice to the already separate Scottish polity that it helped bring into being. Such a seemingly impossible step becomes a little more obvious every day but could also be viewed as part of a clear tradition within the party, and wider Scottish left politics, too.

Breaking free

Labour is essentially a coalition, forced into the straitjacket of a single party structure due to the iron iniquities of First Past the Post. This is an old observation but one worth repeating. The bloc that constitutes Labour in the UK, under a European system, might be made up of several smaller parties, from the centre leftwards. It should have been obvious from the outset that the model of UK Labour would never translate at Holyrood, it was always destined to diminish. The assumption that pre-devolution commentators obsessed over: that Labour’s West of Scotland electoral dominance was unshakeable, turned to dust within a decade.

In Lennon’s leadership pitch there is an understanding that energies can be mobilised when so many remain alienated from the conduct of mainstream politics (turnout at Holyrood elections has never broken 60% – even in 1999). The SNP’s strategic blindness to class politics, and its often panicked response when class springs unbound into the mainstream, offers a potential opening. The party that always seems ‘stronger for Scotland’ has become knotted in the practice of managerialism: corporate lobbyists and landlords all too easily find an influential space close to power as ‘stakeholders.’

There is so much, in fact, that Labour has struggled to acknowledge over the past two decades that it can only hope for any kind of revival in its fortunes through a new foundational moment. There is of course another totemic organisation on the Scottish left that was autonomous from its founding – the STUC.

In 2016 Labour’s share of the vote in Scotland fell to levels not seen since 1918. But there is discontent across the Scottish left. If the party found a way to trace a route back to its origins – seeking in the first instance to represent the interests of those who live by selling their labour – there could be a path back from the brink. It does not lead through Red Morningside.