“Nostalgia doesn’t create good policy. Nostalgia dragging you back to a year that is gone and a place and time that is gone doesn’t give you a good way of looking to the future. The only thing that gives you a good way of looking to the future is looking at what you want to achieve and taking meaningful action on how to get there.”

– Adam McVey, Leader, City of Edinburgh Council

“And many times throughout her life Sandy knew with a shock, when speaking to people whose childhood had been in Edinburgh, that there were other people’s Edinburghs quite different from hers, and with which she held only the names of districts and streets and monuments in common.”

– Muriel Spark, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie

One reason that people choose to live in cities is because they are able to be surrounded by thousands of others with radically different experiences of it. Few cities demonstrate this better than Edinburgh – a capital city that voted not to be a capital city. The AIDS capital of Europe so quickly transformed into the hyper-financialised “inspiring” capital (like most cities struggling with the impact of gentrification today – a concentrated AIDS crisis is a telling common factor). “One of the world’s must-see destinations,” or a city with the same clout as Sheffield or Nottingham – but with a castle, a Parliament and a festival? The Enlightenment’s “Athens of the North,” or Tom Stoppard’s “Reykjavik of the South”?

A mess of diverse contradictions – any city’s past is its greatest resource, and the bedrock of all its imagined futures. But in the city that first gave the historic a leading place in modern life, the public writing-off of collective memory is particularly bizarre. The political leader of Edinburgh claiming that ‘nostalgia doesn’t create good policy’ is a bit like his counterpart in Venice claiming that canals don’t make good policy. Nostalgia, Liz Lochhead’s ‘national pastime’ is fundamental to Edinburgh. To banish it from the debate on what the city is for and might become, represents an act of rhetorical clearance.

The significance of nostalgia to Edinburgh’s culture probably stems from the fact that it was among the first cities in the world to seek to comprehensively remake itself. It is not hard to imagine a kind of longing amongst the first residents of the immaculate and spacious New Town, for the rich social mix of the filthy and cramped Old. It is easier still to think of the first residents of Muirhouse or Niddrie, finding in the promise of urban improvement only a void where community and street culture used to be. With the near-complete gentrification of tenements in the city centre, such nostalgia for the shared space of the close and the back court, seems strangely ahead of its time.

But in their way, Councillor McVey’s remarks are familiar enough. They’re essentially a reheated and localised version of Blair’s 2005 claim that debating globalisation is like debating “whether autumn should follow summer.” There is no alternative, and the loss that many people of Edinburgh feel in relation to their city, is simply inconvenient baggage.

Edinburgh is now undeniably the beating heart of the Scottish economy. Tourism, financial services, food and drink, energy — the holy quartet of contemporary Scottish capitalism are all, in their different ways, fundamentally extractive. They all, despite the Blairite dismissal, remind us of the fact that the awesome irresistible force of globalisation is destructive and unsustainable. Globalisation might be all-pervasive, but it understands the price of everything and the value of nothing. Within this world view, to think that the residents of a small northern European city should get special treatment is palpably unfair. Still, the implicit admission of decline in the city leader’s acceptance that Edinburgh was a better place to live ten years ago – “no shit!” – was unusually candid.McVey was addressing a tourism summit, and referring to a citizen who suggested they’d have preferred living in Edinburgh a decade ago — before the contemporary problems of affordability and overtourism reached their current pitch. Before the symbolic ruin of Princes Street Gardens, before one of the world’s most rapacious hedge funds was given leave to destroy an iconic skyline, before AirBnB turned the Old Town’s tenements into a vast and unregulated playground for rent-seeking.

It is too much, apparently, to imagine the democratic role of a councillor as something other than the guardian of a product: singular and sellable. McVey notes Edinburgh’s place right at the top of ‘liveability’ rankings, as underpinning its draw for tourists. But if local government has no use for the city’s past in policy making, it might at least consider more nuanced views of what a city is for – rather than citing an index created by an asset management firm, which placed the Scottish capital ahead of London and Paris in 2018 (unsurprisingly, given the competition, affordable rents are not factored in here).

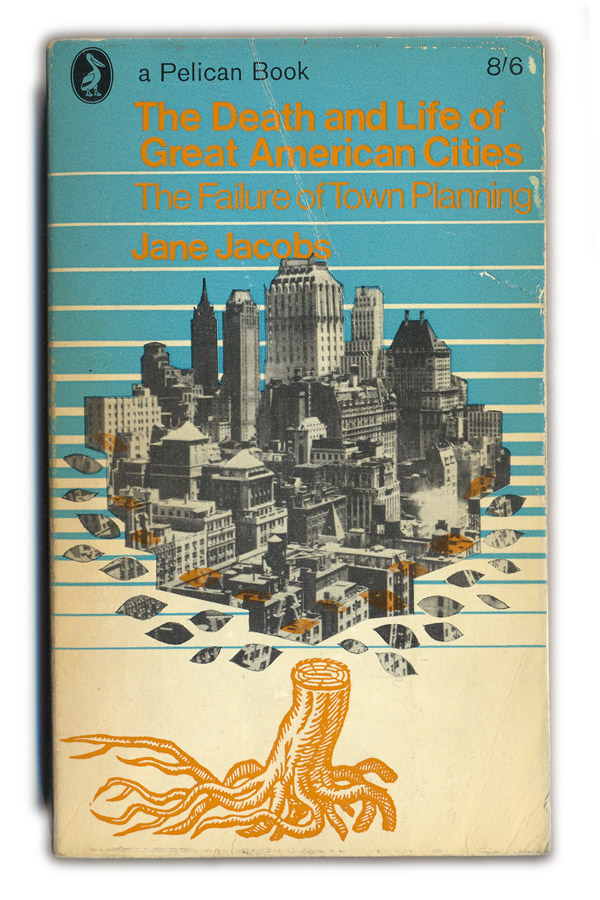

In 1961 Jane Jacobs, visionary critic of mid-20th century urban planning, wrote that the great concentrations of people which define urban spaces: “Are the source of immense vitality…because they do represent, in small geographic compass, a great and exuberant richness of differences and possibilities, many of these differences unique and unpredictable and all the more valuable because they are.”

But for Jacobs this vitality is dependent on relatively stable neighbourhood economies and street life — providing an organic array of local services and public goods that planning seldom achieves, and that dramatic shifts in change of use often destroy. When a city neighbourhood starts to garner a certain level of commercial investment, she notes:

‘… the locality will gradually be deserted by people using it for purposes other than those that emerged triumphant from the competition — because the other purposes are no longer there. Both visually and functionally, the place becomes more monotonous…The locality’s suitability even for its predominant use will gradually decline… In time, a place that was once so successful and once the object of such ardent competition, wanes and becomes marginal.’

Such a process is now writ-large across Edinburgh, and decline can already be seen on the horizon – if you can see past the Deliveroo cyclist running a red light to pay the rent, or weave your way around multiple walking tours jostling for pavement.

When Jacobs published her analysis in The Death and Life of Great American Cities, she was panned across the political spectrum as sentimental and nostalgic – because her views were incompatible with an economic orthodoxy premised on mass rehousing and road building. But as gentrification has become ever more pervasive, these words now speak directly to cities like Edinburgh: fearing that the many shared resources that make urban localities thrive will be irreversibly depleted by tourist monoculture and commercial competition for space.

When the term first came into use, nostalgia was viewed as a medical disorder, a ‘disabling longing for home’ — its literal translation from the Greek is ‘home-pain’. This point is explained in Alastair Bonnett’s Left in the Past: Radicalism and the Politics of Nostalgia, in which he also writes:

‘…if modernity is a time of alienation then all attempts to speak of human sympathy and solidarity are likely to offer a politics of transgression in the form of a sense of loss. We are used to imagining nostalgic longing as akin to reverie, a moment of drooping repose. But it seems it is also a moment of creativity, of discord and danger.’

Whether or not nostalgia creates ‘good policy,’ – it is the vital ingredient in the making of place. Only the most biddable, elitist, politics seeks to dismiss its vital democratic potency.

But the discord of nostalgia jars with the shining future of the city as destination rather than home — where the extractive nature of the tourism industry is presented as a winning gambit in the existential game of drawing multinational capital in. Confusingly, the claim to be a ‘must visit’ ‘bucket list’ destination, is also underlined with the veiled threat of capital flight. Apparently a too assertive populace (in McVey’s term ‘insular’) seeking affordable rents, navigable streets, and jobs in less precarious industries, will be enough to drive the tourist dollar away.

Of course, this totalitarian injunction to openness and welcome — in a famously douce and buttoned-up old city — is, ironically, a call to be like everywhere else. Nostalgia, in contrast, is a great repository of all those particular memories and quirks, represented in the other people’s Edinburghs that Spark/Sandy could never know.

Tellingly, you can’t feel nostalgic about a future destination on a list, mediated through a series of apps and transactions, and so contemporary tourism erodes the basic shared capacity for memory and community that is the basis for citizenship. Without this great mess of diverse and idiosyncratic place-knowledge jumbled together, the urban space dies and becomes merely the ‘average town’ that the city leader warned of in his speech.

In their unhelpful nostalgia for an authentically liveable city, the discontented folk of Edinburgh are not simply pining for bygone rose-tinted summers, as McVey tells it. They are asking what happened to the city as a place of familiarity, community and shared knowledge — they are asking for their home back.